5:30

Commentary

Commentary

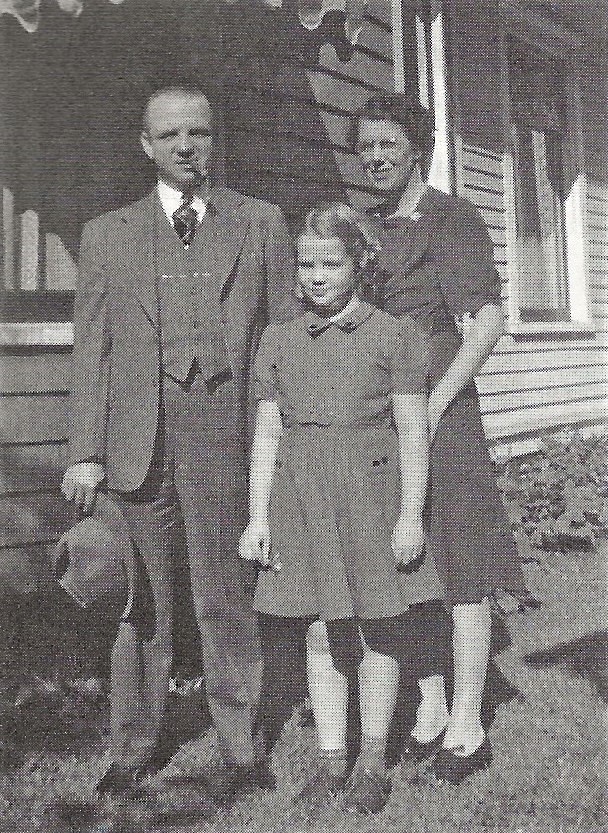

A Kentuckian transplanted to Detroit ‘sat down’ with the United Auto Workers in ’37

They ‘called us communists — and just about everything else you could think of. But it didn’t bother me a particle,’ Ermon Harp told the author.

I saw on Instagram that the daughter of a 1937 sit-down striker at a Flint, Michigan, General Motors plant recently walked a picket line with United Auto Workers strikers at a GM facility in Swartz Creek, Michigan.

“86 years after the sit down strike, UAW members are standing up!”?uaw.union?posted.

I’m sure Western Kentucky natives Ermon and Lube Harp, both pioneer UAW rank-and-filers, would be standing up for their striking UAW brothers and sisters. Ermon was a sit-down striker in ’37, too, but at the Advance Stamping Co. in Detroit.

Historic 1930s New Deal legislation gave most workers the right to form a union. The result was an unprecedented wave of unionizing especially in industry.

Heretofore, when workers struck, they left their workplaces. To defeat strikes, employers typically brought in strikebreakers.

In a sit-down strike, which the UAW helped pioneer, strikers stayed put in their factories. Employers were reluctant to use police or National Guard troops to evict them for fear of damaging machinery. “When the boss won’t talk, don’t take a walk. Sit down! Sit down!” a poem went. “When the boss sees that, he’ll want a little chat.”

The Harps, Carlisle countians from Milburn, retired to Mayfield in 1963. In a 1982 interview, Ermon told me she was still heart and soul with the UAW. “I always will be, and my husband always was, too.”

Lube was 75 when he died in 1970. Ermon died at age 97 in 1992.

She said that back in the ’30s, opponents of the UAW “called us communists — and just about everything else you could think of. But it didn’t bother me a particle. We were the United Auto Workers. We felt like we were doing right.”

The Harps were part of a mass post-World War I exodus of Kentuckians to the Motor City. Lube owned a tiny, less than profitable sawmill. “There just wasn’t any job for a girl around here back then,” Ermon remembered.

Was Harp scared when she joined the strike? “Goodness, no,” she said. “There was nothing to be scared of.”

There was, of course. UAW organizers and members were fired, blacklisted, jailed and even assaulted. The year Harp struck, Ford Motor Company guards severely beat up union activists, including Walter Reuther, the UAW’s president and guiding spirit for many years.

“I remember Walter Reuther, too,” Harp said. “He was with us, that was for sure. He was down to earth.”

Historians say the sit-down strike tactic helped pave the way for union organizing throughout American industry. The most significant sit-down strike began on Dec. ?30, 1936, at the GM plants in Flint, near Detroit. In January, police tried to evict the strikers. Workers repelled them and held on until Feb. 11, 1937, when GM recognized the UAW.

The Flint sit-down inspired the strike at Advance Stamping, where Harp worked. “I had no idea that what I was doing was making history,” she said.

Harp was among about 25 workers who sat down on March 1 at the factory which produced automotive and radio parts. A dozen were women, according to the?Detroit Free Press.

The strike was successful. On March 10, 1937, the UAW announced that the company agreed to recognize the union as the sole bargaining agency for 100 workers, evidently most of them women. They also got a raise.

Harp had a head full of memories — and a bulging scrapbook — about UAW organizing drives. “Our people were getting beat up all over town. But nobody got hurt where I worked. I guess it was because it was a small plant.”

When Harp sat down, she was working on an assembly line, fitting together distributors for car engines. The strike “went off smooth as you please,” she said. “There was no rough stuff.”

Harp added, “People (Lube among them) brought us hot food, blankets and pillows. We organized a square dance. Some of the men played cards, and we turned the radio on to a church service on Sunday. We found some big barrels, put some boards over them, spread down our blankets and slept pretty well.”

Harp recalled that the strikers included a couple who had just gotten married. The newlyweds spent their honeymoon on strike.

Lube had joined the UAW at a General Motors factory where he worked. Harp said she became “union all the way” at the non-union plant where she worked before landing a job at Advance Stamping and eagerly embracing the sit down strike.

“I’d worked there 11 years, when the boss came in one day and said, ‘Ermon, come pick up your check. You’re through.’ Later, I found out he’d given my job to his girlfriend. That’s why I went union and why Detroit went union. It was because of things like that, that wasn’t fair.”

GET THE MORNING HEADLINES.

Our stories may be republished online or in print under Creative Commons license CC BY-NC-ND 4.0. We ask that you edit only for style or to shorten, provide proper attribution and link to our website. AP and Getty images may not be republished. Please see our republishing guidelines for use of any other photos and graphics.

Berry Craig

Berry Craig, a Carlisle countian, is a professor emeritus of history at West Kentucky Community and Technical College in Paducah and the author of seven books, all on Kentucky history. His latest is "Kentuckians and Pearl Harbor: Stories from the Day of Infamy" which the University Press of Kentucky published. He is a freelance journalist, a member of the American Federation of Teachers and a longtime union activist.

Berry Craig